Mariupol citizens Iryna and Serhiy Horbulya told the editorial staff of the Evacuation.City what they experienced in the besieged town.

Before February

Iryna Horbulya's family loves everything related to the sea. The family are Mariupol residents in the second generation and they used to see two sides of the coin in everything.

Mariupol sea

Mariupol sea

On the one hand, factories are terribly damaging the environment; the Ilyich plant and Azovstal spew poisonous smoke into the air. On the other hand, the city lives thanks to these factories. Sergey, Iryna's husband, works hard as a metallurgist but has a stable salary without delays. Like everyone else, they generally have an ordinary good life: family, home, and two small children.

Iryna works as a kindergarten teacher. In the evenings, she goes to taekwondo training with her eldest son. On the way to classes, she often makes an extra lap to walk along the recently built sea pier. The Azov factory-lined area has grown with decent infrastructure for five years. Everything is calm. No worries.

We`ll see

February 24 didn't start well - the couple's eldest son fell ill. The phone has been ringing all morning: taking the youngest to school is unnecessary. There were no classes, then call from work - Iryna still needed to go to the kindergarten but met the children only near the basements.

Iryna rushes to work only to run back literally an hour later. The head of the kindergarten, who lived on the outskirts of Mariupol, can no longer reach the city. She asks to "hand out" the children back to their parents, close the kindergarten, and go home, leaving only the basement open.

Mariupol before the Russians

Mariupol before the Russians

A small grocery store is under Iryna's house, proudly named "Grace".

The woman buys bread and meat just in case - Serhiy will laugh at it at home. Why did she stock up on food? It`s not a year of famine, for God`s sake.

Ira nods but packs the freezer with meat and dries half of the bread on a rusk. Two sealed evacuation bags are waiting in the corridor. Serhiy looks at the preparation process sceptically because the city has no panic. No queues in the shops.

They only heard explosions on the outskirts and siren screams every half an hour. Serhiy remembers that the same thing happened in 2014 – the Russians tormented Mariupol's left bank with the so-called DPR puppets. However, the Ukrainian military was able to recapture the city.

Serhiy's brother calls in the afternoon. He has been living in Poland for several years and insists - come to me, Ukraine is being shelled. However, Serhiy is sure that the city is fortified. No panic. And then answered - we'll see according to the situation.

From 25 to the end of February. Panic at the Pentagon

The district of Mariupol, where the couple lives, locals call gracefully "the Pentagon". When Iryna moved in with her husband after marriage, Serhiy told her – if she looked at the maps of the US Department of Defense headquarters, their block was very similar to it regarding the location of the houses. Ira did not check this; she just believed her husband's word.

On February 25, the Pentagon was the first to remain without power. February's minus is showing its teeth outside the window and the batteries feel like ice. Serhiy and Iryna cover the windows with a warm blanket, so the temperature in the apartment remains at 16-17 degrees for about a week.

The district is holding on with restrained optimism – everyone says you must wait a week, and everything will be over. Gas stoves in apartments work around the clock because there is gas and water. Horbulyas cook almost as normal. They even warm up a bit under the flaming blue fuel.

However, towards the end of February, stores start to run out of food. People flood the rows of counters en masse and take a lot of food, candles, lighters, and matches. There is no new arrivals and sellers are scavenging the last stuff from warehouses. It became difficult to find even bread. Iryna blessed her provisions once more and quickly joined the kilometre-long queue. The last bread was brought to one of the stalls.

Beginning of March. Portcity, rot and rubber glass

March starts at with -10°C. And a humanitarian disaster. On the third day, the mobile connection disappears in Mariupol. On the fifth – water. The sixth – gas.

Gloves and jackets are no longer outerwear – the family has slept in them. Children cry and ask to take off their hats because their heads itch.

Irynas kids

Irynas kids

The woman's parents live in the so-called twenty-third district, at the other end of the city. Even before the connection is cut, Iryna's mother calls in hysterics: the Russians are destroying Kurchatov Street, next to the Pentagon. It's time to take the children and hurry to the twenty-third.

On the third of March, the couple took a risk. The car moves smoothly along the Volodar motorway and two huge shopping centres: Metro and Portcity. Iryna's eyes widen in surprise: crowds of apocalyptic proportions in front of shopping centres. Later she learns that the Ukrainian military has opened both stores - after all, there is no light, the products will spoil. At least for a few days, it is better for people to stock up and have something to eat.

Queues in front of Port City and the Metro have become monstrous

Queues in front of Port City and the Metro have become monstrous

The home area welcomes Ira with chaos: boxes of slow cookers and frying pans that have been taken out of shops are getting wet in the rain and sleet. This dirt also becomes a blessing - the people of Mariupol drag heavy buckets of dark snow into their bathtubs to melt it and get at least some water.

Mum and Dad's house is stable at -2°C because all the windows are already blown out by the blast waves. The family moved to Ira's brother's apartment, which still had windows. He is a military volunteer and left the city on February 25.

That day Serhiy goes to Port City to get some groceries. A vast shopping center lives in darkness. There is a disgusting smell of rot in the air. The man's flashlight illuminates crushed eggs and rotten fish on the floor. People are moving all over Port City, trying to rake in the dark and bring at least something valuable to the family. In some stores, Serhiy finds a warm jacket and sweater and goes home - there is no point in looking for products. On the way, he hears a specific whistle and dives into an arch near the store.

In a second, a shell flies into Port City. Serhiy sees a huge shopping centre on fire. He has just been there, and there are still many people there.

Almost everyone who did not manage to run out died that day.

Ira sees everything that has happened to him without words: it is all there on the man's chalk-white face when he returns home.

And the jacket that Serhiy caught in Port City turns out to be yellow and blue.

The same jacket

The same jacket

Later, the husband's parents fly in; they have just survived the bombardment and are willing to drive anywhere to get away, so they pile into the father-in-law's car, registered in 1975, and drive back to the Pentagon.

Pentagon lights

Ira and her family had only been home for two days, but the Pentagon had changed for the worse. Ira is shivering - partly from the cold, and she can't hide that feeling under any jacket. Part of it comes from feeling like she's on the set of an apocalypse film. But somehow she can't get off the stage.

Since 6 March, fires have been burning constantly in the streets. The people understand that there is no one left to turn the gas and the heat back on. Ira sees the neighbours ransacking the shops, looking for slow cookers, but taking out everything that can burn. Hence the pieces of countertops in the street.

The fires started burning at five in the morning

The fires started burning at five in the morning

People are taking apart entire entrances. Flats with wooden doors are particularly vulnerable. The intercom does not work, so the people of Mariupol try to close the gates with at least some bolts. It does not help. Serhiy takes apart a beautiful sofa from someone's flat and marvels at how quickly everything except food and clothes has lost its value.

The Pentagon has its strange routine: from five in the morning, the streets are filled with people with pots and pans. Light a fire, put a pot of soup on and run away - the dynamic is the same for everyone.

Nobody goes out in the evening. So they have to cook with a reserve and find a way to keep the food warm. Ira takes a large double bedspread and turns it into a thermos flask. Hostages in their own city, people started to put plastic bags on the plates – so they could eat soup for longer from relatively clean dishes, just by changing the polyethylene each time.

Water is precious, as there is only one well in the Pentagon. Everyone knows that shrapnel killed someone near it. That's why several neighbours always go there, so that if anything happens, they can at least bring the injured home.

Birthday party

On 16 March, the Horbulyas go to the birthday party of an 82-year-old neighbour. In the flat opposite, the couple were greeted by a huge ball of fire. From the windowsill, a red-hot projectile flies directly at Serhiy: the man is carried out into the corridor by an explosive wave.

The blast wave pushed Ira against the closed door. The woman is surprised that the door has turned to paper - only paper can burn so quickly and easily.

The legs do not hold her anymore. Later, Iryna will ask herself if it was a contusion, but for now, she is lying on the floor, pressed by the whole weight of the world. Ira feels the glass dusting on her teeth.

The second bullet is already flying, but Iryna and Serhiy, covered in concrete snow, sneak into their apartment in the dark - because there are children there. They don't have time to open the door - the peephole flies out and whistles through the flat.

The eldest son crawls towards them, looking for his parents. The child is crying. The parents have blue lips and aching hearts.

The younger son sits quietly in a corner and looks at them. Then he crawls over to the toys and begins to play quietly.

Cellars

If something whistles, it is better to drop face down. The main thing is to get as close to the ground as possible, so that the shrapnel passes you by.

An aeroplane always comes at night. The whistle means the bombs are about to fall.

The youngest son asks Ira: "Mum, why do you lie on top of us at night?

Mum, why are you lying on top of us?

Mum, why are you lying on top of us?

Now the whole Horbulya family lives in the cellar. Ira persuades her husband to go to the drama theatre, because she hears there are buses to Zaporizhzhya. Serhiy denies it - the shelling is so intense that it is impossible to turn back. In a few days, friends will say – Drum has been bombed.

On 18 March, some families go to the garages, take their cars and leave. Serhiy also leaves – but returns with nothing. Horbulya's car was no longer in the garage. By mid-March, people were stealing everything they could.

Only the Horbulyas, pensioners and small children remain in the bombed-out house. They are trapped.

Ira and Serhiy feel such emptiness, as if each of them has a small black hole inside.

One evening, soldiers from the Ukrainian Armed Forces hid in their house. They ask people not to say anything to anyone. The DPR puppets have a simple tactic - they do not risk their lives. They just drive a tank to a house where they think there are Ukrainian soldiers, and from there they shoot each person, the house and everyone inside.

Mariupol Drama Theatre after the bombing

Mariupol Drama Theatre after the bombing

On 26 March, a man from the so-called DPR approaches Ira and says that the same fate awaits them. He shows his "republican passport", but quickly takes it away, just like in the films. At first, Ira does not believe him.

An hour later, the shelling begins. Men from neighbouring houses help Serhiy to extinguish the fire with whatever water is left on the outskirts of the house. To Ira's surprise, everyone has survived.

Tonight they make soup from all the leftovers in one pot. They feed the children first, then take turns to eat. All the inhabitants of the burnt-out cellar eat from the same spoon. The food had been rotting for a long time.

Now they all gathered in the flat next to the retaining wall. Blankets, cushions and stools were worn out, and children were placed on them like dolls or soldiers. Adults huddle together like jigsaw puzzles to keep a little warm. It is a moment of strange, unsettling stillness – waiting for the next bombardment.

The way to Sartana

The morning of 29 March began with Russian soldiers. They burst into the driveway and warned that they would thoroughly destroy the house.

Ira and Serhiy looked at each other. They know that at 19 Metalurgichna Street 40 people were shot in this way: they buried them all in the cellar. There was a children's room.

The Pentagon. The second month of the war

The Pentagon. The second month of the war

The people from the Pentagon go into the street after the Russian soldiers. Everyone is told to wear white bandages – without them one cannot survive the fire of the snipers who nest on the rooftops of Mariupol. The Russians themselves have a flaming Z on their bandages.

Ira moves as if in a fog. The March frost penetrates her bones. The woman no longer understood where she was being taken, why, or what was happening. The couple gave the children to their parents – the Russians let the pensioners go first. It takes Horbulyas just five minutes to understand the reason for this act of kindness – russians stopped all men under the age of 60. And they have no interest in pensioners.

Sergey is humiliated. Russian soldiers rudely force everyone to undress – looking for tattoos that indicate membership of the armed forces, or marks from a machine-gun belt. The line of Mariupol residents is dragged along, the men standing naked to the waist in the biting wind. When they are finally released, they are told to go to the Volunteerivka settlement near Mariupol.

Without a white armband, there is a high probability of being shot by snipers

Without a white armband, there is a high probability of being shot by snipers

A battered little bus – the Illichovsky "pazik" – waited for them there. 40 people. Only then did the Russians bring in up to 200 Mariupol residents, gathered from the entire neighbourhood.

Suddenly a "media star" emerges from the nearest house – that's what Serhiy calls this man. Although the Soviet word "chief" would suit him best. The "chief" tells wonderful stories how Russia will save everyone. After all, she, Great Mother Russia, will feed them, keep them warm and protect them from the Ukrainian Nazis.

Then a comedy unfolds before the couple's eyes: soldiers carry benches and two 20-litre water containers from nearby houses. A woman's nose is bleeding, and cotton wool and hydrogen peroxide are carefully brought to her. Children are ceremoniously presented with sweets and biscuits.

Hungry, nervous, disoriented adults sit on benches and greedily drink water, accompanied by promises from the Russian military. The "chief" says: "Everyone will be taken to Sartana, a settlement near Mariupol. There they will be warm and fed.

Sartana

The bus is full. Iryna has two children in her arms - only people with babies sit, everyone else lies on top of each other in the aisle. The trip to the settlement is short, 20 minutes. But the bus makes several trips because it is physically impossible to pick up two hundred Mariupol residents from the first trip with a broken pazik.

Everyone is unloaded at Sartan, near the military command post of the occupiers, to wait in the cold wind. And here the image of good Russian soldiers ends.

a broken piece of neighbourhood

a broken piece of neighbourhood

The first to be taken out of the bus was a seventeen year old boy. The barrel of a machine gun rests on his back - he is accused of feeding Ukrainian soldiers. The Russians take him to the commander's office, with the machine gun between his shoulders. Ten minutes later, the boy walks away - lying that the Ukrainians forced him to feed them and that he had no choice. The Russians believed him, but promised to shoot him without trial or investigation if they found out he was lying.

Iryna tries several times to talk to the Russian soldiers, to ask what will happen next - but it's no use. At first they try to answer the questions calmly, but within a few minutes they literally burst into curses. This is the first time Iryna hears the word "filtration", and without this magical "filtration" they are nobody and nothing on the territory of the so-called DPR.

Suddenly, the soldiers announce that the village is full of people. Who has relatives in Sartana? Ask them about accommodation. Who doesn't have one – find something anyway; maybe we'll take you to empty kindergartens and schools – but first you have to go through filtration.

As the Russians make this speech, a bread machine appears out of the mist. Hungry and tired people reach for food, but bread is only given to children under twelve - one Russian takes a loaf by the handful. As much as he tore off, as much went into the children's hands: no knives or gloves. A military man walks by with a phone and records the distribution – the queues and the van, but not the process itself. That evening a story about good Russians is to be made for Russian television.

Sartana after the Russians

Sartana after the Russians

Last trip to Mariupol

Iryna is doing the dishes and listening to the Russian news behind her back. The announcer says: "Hurrah! Good Russians have brought great humanitarian aid to Donetsk. Now the people of Donetsk can take home household appliances: washing machines, fridges and televisions.

The woman grimaces in disgust. Yesterday she saw huge lorries leaving Mariupol, overflowing with other people's furniture, washing machines and fridges.

Russian ‘humanitarian aid’

Russian ‘humanitarian aid’

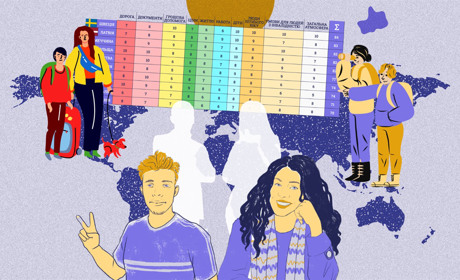

She and Serhiy thought for a long time about what to do next. They had lived in Sartana for a week, observing the local order. The queues for filtering in Bezimenne stretched for several kilometres: rumours reached Sartana that waiting for your turn in a tent city could take from two days in good conditions and up to ten days in bad. Those who did not go through this process disappeared into the cellars. At the family meeting, the family decided to walk to Mariupol, leaving the children with the husband's parents, to see what had happened to the city in the last two weeks.

The family has a secret they don't tell anyone - a stash of cash, locked away in the walls of the garage. The family did not want to go anywhere without it.

So on 12 April, the they walked to Mariupol.

From the garden near Serhiy's home, the people of Mariupol can often see their city being bombed from Sartana. The ghouls shudder at Azovstal's metallic groans, but they can only watch as the fireballs fly towards their homes again.

Azovstal

Azovstal

And it's easier to leave. So, for now, the people of Mariupol seem to have something of their own - at least the freedom to return home, at least occasionally.

The family walks through Volonterivka, black with smoke, to their pentagon.

Serhiy looks around and does not recognise the neighbourhood of his childhood: there are piles of rubbish everywhere, and among the rubbish there are homemade crosses and hungry dogs tearing at them. The couple are afraid to take a closer look. The people of Mariupol bury their dead under their houses, but it doesn't go deep - you have to run away from the shells to avoid falling into the same grave. Hungry dogs take advantage of the situation.

The family understands: they have to take money from the garage and leave. Mariupol no longer exists.

Garage and preparation for filtration

If the couple had known that their garage was surrounded by the DPR "guard," they would have been afraid to go there. But they didn't know that, so they sneaked into their garage. The DPRs are unusually busy—greedily looting things that do not belong to them. Twice, the Horbulyas come to their garage, and twice, they are turned back, but during this time, the couple develops a whole plan for evacuation.

In Sartana, the Horbulyas were able to buy a Russian phone card – from people who already gone through filtration and survived it. These people said that the rumours about the Bezimenne were true. The Russians extract the entire phonebook, messenger correspondence and gallery from smartphones, and even restore deleted ones with special programmes. People who had at least some sympathy for Ukraine disappeared into the cellars.

But the risk is there, and it is quite high.

It is impossible not to pass the filtration – without it, any Russian soldier can stop you anywhere in the so-called "DPR" and start abusing you: undressing you, checking your phone, interrogating you. To get out of this grey quagmire, the Horbuls need two identical pieces of grey paper with notes on successful filtration.

After the first trip to Mariupol, Serhiy was able to call his brother in Poland and tell him they were all alive. The family immediately gave the Horbulyas a plan of action if they managed to enter Russian territory: they gave the numbers of volunteers who would take Ukrainians from the Federation and evacuate them to Europe. There was no possibility of going to unoccupied Ukraine.

Mariupol in April

Mariupol in April

Irina received a message from her mother - and her heart warmed a little. It turned out that her brother's acquaintances had taken her first to Russia and then to Germany, and now her mother was safe.

On 22 April, as the Horbulyas stand outside their garage for the third time, they have already decided to go to Bezimenne and are slowly getting ready: they are wiping all the data off their phones and working out their answers for the Russians.

The Horbul's don't know how long they'll have to stay on this filtration, so the couple take whatever food from Mariupol they can salvage from the Pentagon: a packet of burnt macaroni, some battered tins and even a packet of soot-black lard. Iryna brings some summer clothes for the children from home.

This time there is a man from the so-called DPR near the garage; the couple persuades the soldier to let Serhiy into the garage for at least two minutes – Iryna remains waiting for her husband at the gate and has a conversation.

The young man turns out to be from Donetsk itself. The boy describes the events in the city with the words "tuff", "bullshit" and "it used to be better". In 2015, he was drafted into the DPR army and found nothing better than staying there.

All in defence of our homeland, Donbass! Propaganda on the stands in Donetsk

All in defence of our homeland, Donbass! Propaganda on the stands in Donetsk

While Iryna carefully answers the boy's questions about their apartment in Mariupol, Serhiy nervously smashes the garage wall with a crowbar - the man has forgotten which brick he put the family's money behind. Time is against him - the watch on his hand shows that seven minutes have passed and he could have been there for only two. At the moment of greatest desperation, a black metal box containing the savings appears under the crimson pile of dust - the man quickly hides the money behind his shirt and rushes to Iryna.

The woman sees Serhiy from behind the gate and notices that he is holding the hem of his shirt. The boy asks no questions - and the people of Mariupol quickly return to Sartana. Everything went well, but the next item on the list was the filtration itself.

Bezimenne: filtration

At the end of April, the entire Horbulya family – Iryna, Serhiy, their two small children and her husband's parents – queued up for the filtration buses.

Trucks full of bedridden and disabled people drive past them – the Russians are taking disabled people from Mariupol and pushing them around the local churches.

The Horbulyas are scared. But they are ready at the same time. Their turn for the bus queue is the last. And strangely enough, it helps them. In Bezimenne, they were the first to accept their loan for filtration.

Filtration process

Filtration process

The pre-filtration room is an old Soviet school. The gym is crammed with rusty beds. There are no mattresses, just bare metal nets – when anybody tries to sit on them, they automatically sink to the floor.

Down the corridor from the gymnasium is the school canteen, where, surprisingly, hot meals are served. The only condition is to endure the smells, which stick to the skin like flies to sticky paper.

The couple happened to come across a short mattress and a Pilates mat – they put the children on it and lay down on the metal nets without sleeping. They can't close their eyes, even though their bodies are tired. Iryna is afraid of tomorrow.

But tomorrow is kind to her – without explaining why, her whole family and several other people are taken from the stricter FSB Bezimenne to Starobeshevo. As the people of Mariupol already knew, the regime is a little more lenient there. Full of hope, the Horbulyas get into the bus.

Starobesheve

Starobesheve and Bezimenne are about an hour and a half away by car. On arrival, the Horbulyas are taken to the old House of Culture. The familiar stench of excrement greets Mariupol residents - now the toilet surrounds the building instead of hiding behind it.

The family sinks into the broken and twisted seats, which retain some dignity only because of the red velour upholstery. Some are sleeping on the stage, others are lying on the floor.

Starobesheve

Starobesheve

Then things happen very quickly. Iryna and Serhiy are separated from their male parents - their passports have been taken from the pensioners - and their spouses' children, and divided into different lines.

Serhiy is taken to the police station. First, a man fills out a questionnaire with the classic questions about age, profession and marital status. And, of course, the FSB: about attitudes towards Ukraine and possible links with the Ukrainian armed forces.

In the next room, Iryna fills in the same questionnaires. The woman from Mariupol knows that women's opinions aren't often taken into account - so she writes "I am neutral" before the question about Ukraine.

Simultaneously, but in separate rooms, the Russians took the couple's fingerprints and photographed them like burglars. Smartphones had been taken from both of them earlier. Horbulyas deleted the entire phone book in the hope that conversations could not be recovered.

Irina knows that Russians look down on women, but they don't force anyone to undress – at least not in her line. Ironically, as the sister of a military volunteer from Mariupol, she does not arouse suspicion among the occupiers.

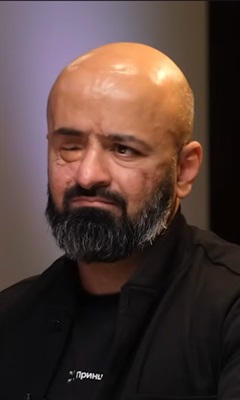

It is more difficult for Serhiy. It seemed to him that he would no longer be surprised by anything. However, he still stifles his inner indignation when Russian soldiers force him to undress, examining every centimeter of his skin. But one has to suppress his disgust to survive – and it works. Russians released him. Now both residents of Mariupol have grey filtration pieces of paper – tickets to freedom.

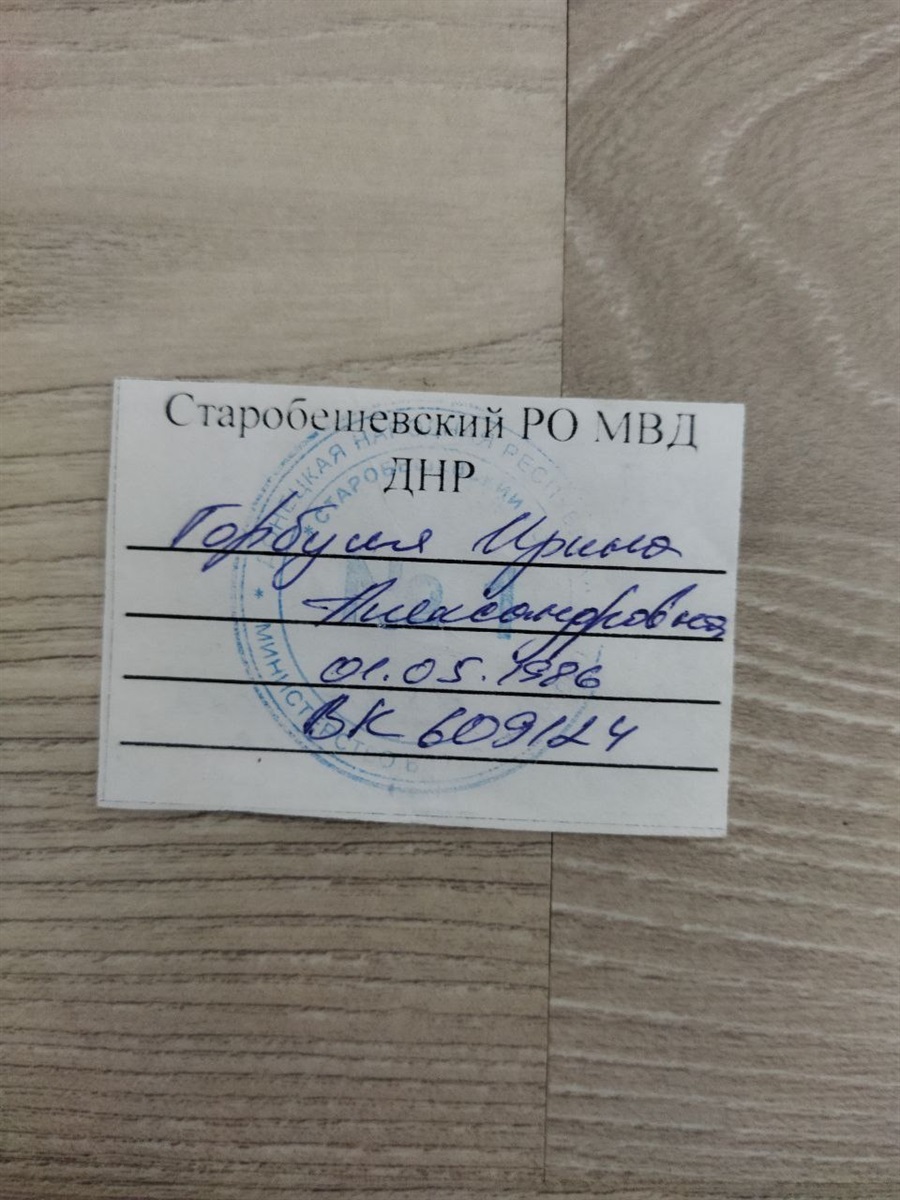

filtering ‘document’

filtering ‘document’

Taganrog, Roma money changers and volunteers

Iryna has been waiting for her husband with her in-laws and children for a long time - millions of times, Russians tried to get her on a bus alone, saying that her husband would arrive later. However, the family waits silently – and politely rejects all these offers. The passports of Serhiy's parents were returned earlier – Russians paid very little interest in pensioners. When Sergiy approaches the family, Iryna barely holds back tears – freedom seems close, but they are still afraid to believe in it.

The Horbulyas are lucky again - after successfully passing through the filtration process in two hours, where people wait ten days to avoid the cellars, they immediately get on the bus that takes the Ukrainians to Russia.

It is such a rare story that they wait a few more hours for at least a few more people to arrive - so that the bus does not run 'empty'. In the meantime, Serhiy and several other men were asked to bring in a disabled woman who was lying on the floor. She also went through the Russian filter - and was placed in the corridor.

Serhiy is happy because he was expecting the worst. But at the Russian border, it turns out that the Russians have an additional filtration for men. The old colonel keeps everyone in a private conversation for at least half an hour.

Finally, the people of Mariupol have crossed the Russian border. It feels bizarre for them to be happy about this, but as they walk half a kilometre to the tent city, the Horbulyas already know - they have done everything for their freedom.

In the town, friendly Russians are actively pouring hot tea for the Ukrainians, although they are not feeding them, and giving another Russian phone card. The Ukrainians were wary of such sharp kindness - and later they would understand that, as usual, their intuition had not let them down.

Taganrog administration lights up the windows of its offices in the shape of the Russian swastika

Taganrog administration lights up the windows of its offices in the shape of the Russian swastika

Unexpectedly, Kyivstar appears on Ukrainian SIM cards - the people of Mariupol start frantically checking the news and texting their relatives until the bus arrives in Taganrog at two o'clock in the morning.

At half past four on 30 April, the people of Mariupol arrive in the Russian city. Iryna is delighted to see civilisation: hot water and rubber slippers to take a shower. Volunteers hand out disposable towels, direct them to the canteen, show them where to pick up second-hand goods and offer dry rations. And they smile and promise that everything will be fine now, that Russia will take care of everything. The Horbulyas look at each other in silence – the people of Mariupol know very well that you can't tell anyone about your plans here.

The people of Mariupol are very grateful and refuse generous offers to go to Sakhalin. A complicated legend about relatives in Moscow frees them from having to explain anything else to the pro-Kremlin volunteers – so the Horbulis board a train to Rostov, having first exchanged hryvnia for rubles at the local Roma rate. They must go to the abode of evil from Rostov – Moscow itself.

From Moscow to civilization

All the while, Serhiy is quietly keeping in touch with the volunteers his brother put him in touch with. A woman in Moscow buys them tickets to the Russian capital from afar - after all, you can't buy tickets online without a Russian credit card. The people in Mariupol give her the money later in cash.

Volunteers oversee the Ukrainians' entire journey - an attentive driver comes to meet them at the station and takes them straight to the temporary shelter for the day. The home of the man who protects the people of Mariupol is not far from the lights of central Moscow - but as soon as the car leaves the heart of the Axis of Evil, the Ukrainians see rows of grey and tattered boards.

A few metres away from the centre, Russia no longer looks so presentable

A few metres away from the centre, Russia no longer looks so presentable

The volunteer gives the Horbulyas a room. The family was able to take a normal shower and eat hot food – the Muscovite listens to their story and repeats with shock that the information in Russia is completely different. He is ashamed to repeat out loud the stories of Ukrainian fascists.

In the morning, at six o'clock, a car arrives for the Horbulyas and takes them to the Estonian border. The people from Mariupol are not alone in the small minibuses – a girl from the Luhansk region is travelling with them, also evacuated through Russia. In a few hours, the Ukrainians reach the border with the Baltic states. In Lithuania, they join a huge queue of cars trying to leave the country. FSB agents scurry between the vehicles, and volunteers change their plans on the way - they head for the Estonian border.

Surprisingly, there is no queue - and no FSB. On 30 April, the people of Mariupol crossed the Russian border and found themselves in European Estonia.

Free at last.

Poland

On this cold northern night, the Horbulis spend the night in the yellow houses of the Estonian border guards. Some of them speak Russian and are shocked to hear the story of the Ukrainians.

In the morning, the people of Mariupol are taken away by the European volunteers who took care of the Horbulis after the Russians; the next night, the tired travellers spend the night in Tallinn.

Volunteers will take Horbulis to Poland, to her husband's brother. The first of May is usually hot in Mariupol - but here it is cold. The Poles bring the Ukrainians clothes en masse so they don't freeze, and help them fill out all the documents for temporary protection in one day. The children find places in kindergarten and school almost immediately, the husband gets a job and Ira herself is offered a place as a teacher's assistant. The whole family is enrolled in Polish classes.

Ira knows she should be happy, but a black fog of depression has descended on her and Serhiy. Everything that has happened since February has suddenly come back to haunt them, as if they had been waiting for it.

The apartment the Mariupol residents rented after receiving their first salaries is near the airport. When planes fly low, they make a low hum. Iryna covers her ears and breathes – no need to fall to the floor, no matter how frightening.

At the end of June, the black depression slowly loosens its grip. The people of Mariupol begin to notice the sun, to rejoice in safety and to allow themselves to live.

Iryna and Serhiy still follow the news from their hometown and send money to the army.

But they no longer see the glaring lights of the Pentagon.